TL;DR: aside from a few exceptions, only mobile web campaigns running in Safari are affected.

iOS 15, released to the public last week, advances Apple’s ongoing effort to enhance user privacy with native features which go above and beyond other platforms. For mobile marketers, a significant new development is Private Relay, which promises to anonymise user IP addresses.

This has caused a stir in the performance marketing space, where IP address is relied upon for various aspects of ad campaign success. On the innocuous end, it’s useful for geo targeting and reporting. In addition to this, most app user acquisition campaigns continue to rely on IP for probabilistic attribution via Mobile Measurement Partners (aka. 3rd-party fingerprinting).

So has Private Relay nuked fingerprinting, and brazenly taken geo targeting and reporting along with it? In short: no – but there are some specific cases to consider.

Private Relay primarily applies to Safari connections, not apps

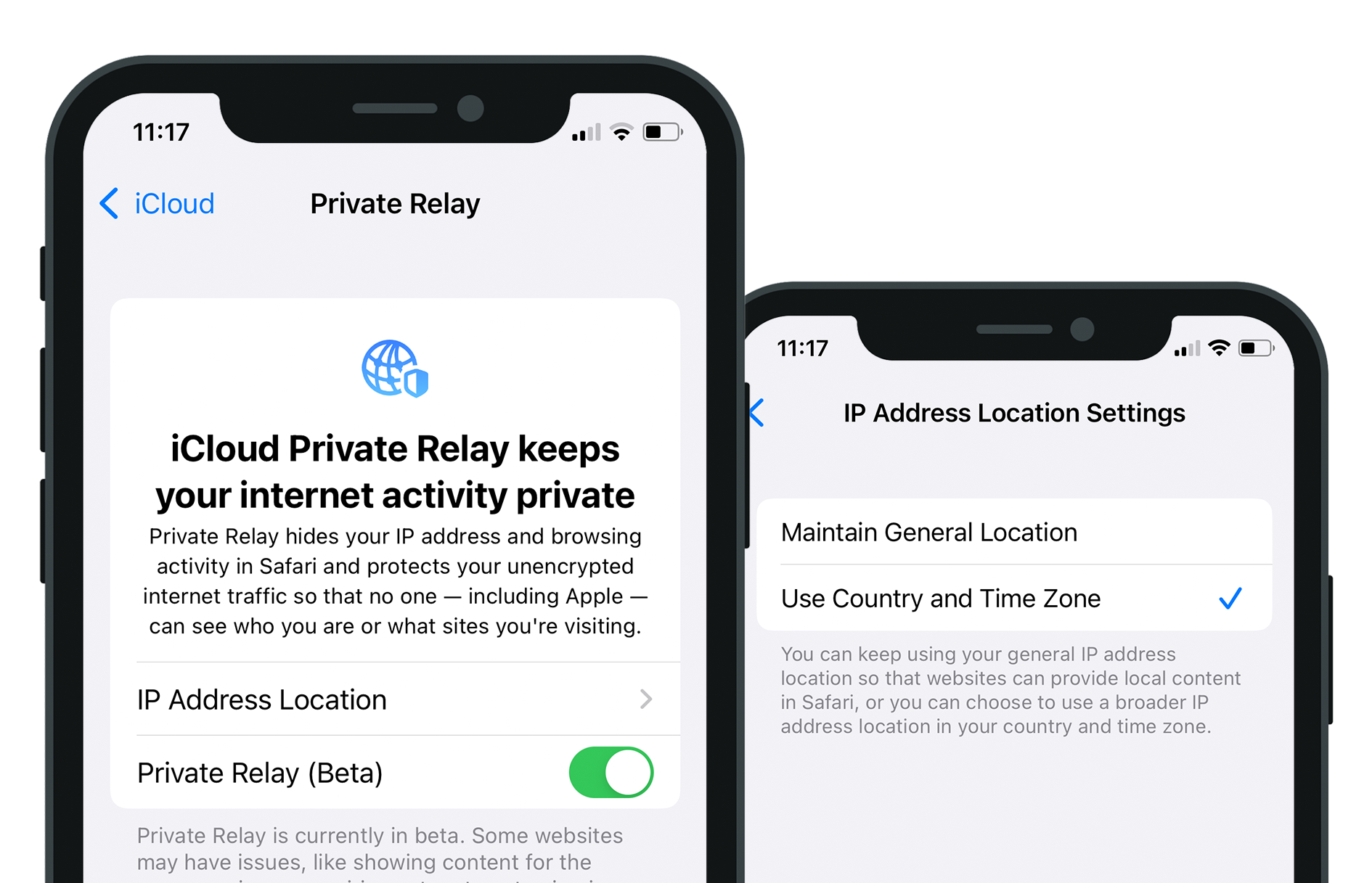

Private Relay primarily impacts Safari: for users with Private Relay enabled, connections made from websites accessed in Safari will be routed through Private Relay. The implication for marketers is that mobile web campaigns running in Safari will no longer have access to accurate user IP addresses.

However, this does not close the door on granular location targeting in Safari, as Private Relay is cleverly equipped with the setting “Maintain General Location” (enabled by default), which ensures the IP address will match the approximate region of the user. Our testing revealed that this was accurate to the nearest large town. When “Maintain General Location” is not enabled, the IP will match the user’s country and time zone – so accurate country-level reporting remains unaffected even in the worst case.

Private Relay does not affect connections made by apps, except “insecure http app traffic” (connections not using HTTPS), and DNS resolution queries. As HTTPS has been standard practice for many years, this is unlikely to affect most app developers. Marketing campaigns which rely on retrieving accurate IP addresses in apps are largely unaffected.

The same is true for Web Views: secure traffic made from a Web View inside an app is not affected by Private Relay.

So in summary: geo targeting and geo reporting are mostly unchanged, unless you’re running mobile web campaigns in Safari, and your campaign relies on very granular targeting – below the level of towns. Equally, 3rd-party fingerprinting also remains largely unscathed for tracking between apps. However, ads which trigger a redirect via the browser will be impacted: with Private Relay proxying the redirect if it occurs in Safari.

What’s next?

A big question is whether – or when/how – Private Relay will be applied to in-app traffic. This would be one very effective method of enforcing a ban on fingerprinting, allowing Apple to nix a prevalent work-around which currently negates some of the consumer benefits promised by App Tracking Transparency (ATT).

But doing so would come with significant challenges: the cost would be significant, as this would be similar to giving all iCloud Plus users a VPN, which proxies device-level traffic. Does Apple want to protect your IP address so much that they are willing to route your next Netflix addiction through their infrastructure? If so, are they willing to offer that as part of a $0.99 subscription, when actual VPN services charge ~4X that?

If Apple offers an upgraded version of Private Relay which covers all traffic on the device, it may make more business sense for this to be included as an opt-in setting in a higher paid tier of iCloud Plus membership. This would constitute a highly marketable OS-level privacy benefit which provides more privacy-conscious consumers with some of the benefits of a VPN, while also avoiding the significant costs of offering it to all users.

Notably for marketers, addressing concerns surrounding ATT workarounds like 3rd-party fingerprinting does not actually rely on a Private Relay change. Another option available to Apple is to enforce more stringent checks during App Store reviews, to limit the use of user meta-data which drives these practices. This was noted to some extent during the initial rollout of ATT in spring 2021, as various stories emerged of apps being rejected. However, the level of enforcement has since cooled off – for now.

In terms of plugging the gaps in ATT, if it’s a choice between proxying device-level traffic vs. policing apps more closely on their way into the store, one of these certainly looks more attractive from a cost vs. effort point of view.